Up and down

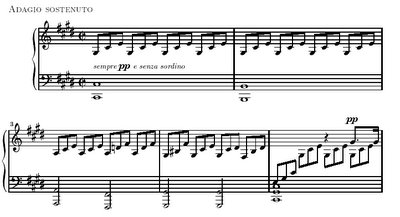

Most music we hear is dynamic. That means, it progresses from one stage to other(s) stage(s). In this music melodic material ascends or decends. If a melodic material holds a static position at a given time, it will eventually ascend or descend. These simple statements make possible some interesting compositional techniques. Let's take a glance, for instance, at the first 5 measures of Beethoven's moonlight sonata.

The first measure seems to be static. The right hand repeats 4 groups of three eight notes, and the left hand plays an octave. The 3 eight note group the right hand repeats has an ascending direction.

The first measure seems to be static. The right hand repeats 4 groups of three eight notes, and the left hand plays an octave. The 3 eight note group the right hand repeats has an ascending direction.

Repetition of this pattern creates the need of something happening to it, resolving it. Since the pattern is an ascending pattern, its natural resolution would be like this:

Repetition of this pattern creates the need of something happening to it, resolving it. Since the pattern is an ascending pattern, its natural resolution would be like this:

Beethoven uses the need of something to happen as a tool to create tension. Instead of having the right hand ascend, is the left hand which descends at bar 2.

Beethoven uses the need of something to happen as a tool to create tension. Instead of having the right hand ascend, is the left hand which descends at bar 2.

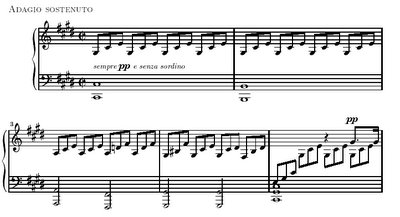

Left hand has descend to B, seventh of the chord. Since the seventh is at the bass, there is an harmonic need for the left hand to keep descending. Meanwhile, the right hand has kept repeating the 3 note pattern, raising the need of an ascending resolution. A conflict has been created: left hand claims for a descending resolution, while the right hand claims for an ascending one. Both hands follow these need at the first half of bar 3. The bass goes to A and the lower note of the right hand pattern goes from G sharp to A. At the second half of bar 3 we have a D mayor chord, a neapolitan chord. This chord creates the need of resolving D, which is played by the right hand, with a descending movement. But the right hand has just started its ascending movement, which was needed because of the 3 note pattern! The next bar shows a dominant seventh chord, which's upper note is the seventh. This note calls again for a descending resolution. The melodic material of the right hand has claimed for an ascending resolution since the beginning of the piece, and at the time it starts ascending the harmony of the piece forces the right hand to descend. And that is what happens at bars 4 and 5. At the second beat of bar 5 the right hand material takes again its original position, as if it prepared itself for a new ascension attempt. The development of this conflict will shape this movement, and even the hole sonata.

You can download the score of this music from sheetmusicarchive.net. You can download a midi file of this and every beethoven sonanta following this link. If this subject is of your interest I recommend you download the score and play it at the piano.

The first measure seems to be static. The right hand repeats 4 groups of three eight notes, and the left hand plays an octave. The 3 eight note group the right hand repeats has an ascending direction.

The first measure seems to be static. The right hand repeats 4 groups of three eight notes, and the left hand plays an octave. The 3 eight note group the right hand repeats has an ascending direction. Repetition of this pattern creates the need of something happening to it, resolving it. Since the pattern is an ascending pattern, its natural resolution would be like this:

Repetition of this pattern creates the need of something happening to it, resolving it. Since the pattern is an ascending pattern, its natural resolution would be like this: Beethoven uses the need of something to happen as a tool to create tension. Instead of having the right hand ascend, is the left hand which descends at bar 2.

Beethoven uses the need of something to happen as a tool to create tension. Instead of having the right hand ascend, is the left hand which descends at bar 2.

Left hand has descend to B, seventh of the chord. Since the seventh is at the bass, there is an harmonic need for the left hand to keep descending. Meanwhile, the right hand has kept repeating the 3 note pattern, raising the need of an ascending resolution. A conflict has been created: left hand claims for a descending resolution, while the right hand claims for an ascending one. Both hands follow these need at the first half of bar 3. The bass goes to A and the lower note of the right hand pattern goes from G sharp to A. At the second half of bar 3 we have a D mayor chord, a neapolitan chord. This chord creates the need of resolving D, which is played by the right hand, with a descending movement. But the right hand has just started its ascending movement, which was needed because of the 3 note pattern! The next bar shows a dominant seventh chord, which's upper note is the seventh. This note calls again for a descending resolution. The melodic material of the right hand has claimed for an ascending resolution since the beginning of the piece, and at the time it starts ascending the harmony of the piece forces the right hand to descend. And that is what happens at bars 4 and 5. At the second beat of bar 5 the right hand material takes again its original position, as if it prepared itself for a new ascension attempt. The development of this conflict will shape this movement, and even the hole sonata.

You can download the score of this music from sheetmusicarchive.net. You can download a midi file of this and every beethoven sonanta following this link. If this subject is of your interest I recommend you download the score and play it at the piano.